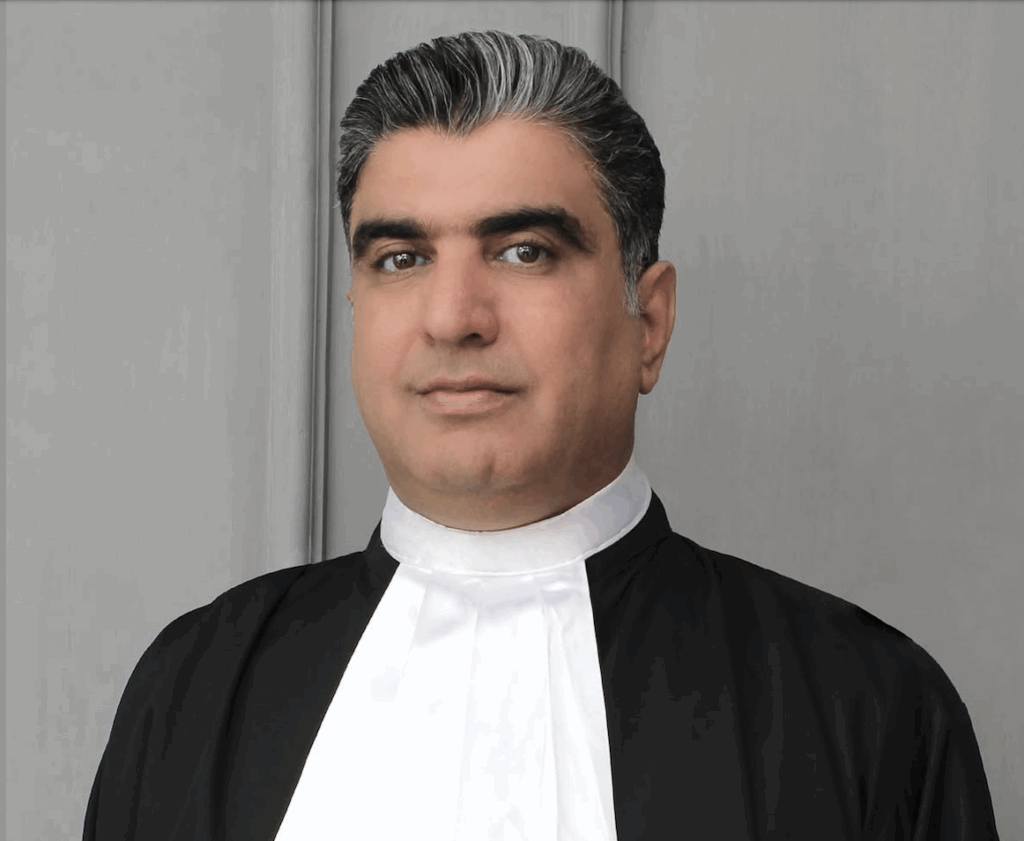

Colombian human rights lawyer Rommel Durán: “A ‘social genocide’ is taking place in my country”

The Colombian human rights lawyer Rommel Durán Castellanos recently spent several days in England and the Netherlands to rally support for his colleagues, who are exposed to threats and violence. Another aim of his trip was to prepare for the international observation mission ‘Caravana Internacional de Juristas’, which will visit Colombia in August for the fifth time. The biennial delegation will consist of a large group of lawyers, judges and public prosecutors from more than ten countries. The ‘Caravana’ is being organized from London, in cooperation with Colombian lawyers. As in previous years, Lawyers for Lawyers will also be represented in the delegation. We spoke with Rommel about the difficult position of many lawyers in Colombia.

Rommel is regularly subject to intimidation and threats and has been arbitrarily detained twice. He seems to speak about this almost light-heartedly but then falls silent: his brother was murdered in 2016. Despite that, human rights lawyer Rommel Durán continues to fight for justice in Colombia.

“No” he says, smiling but serious, in the interview with Lawyers for Lawyers. He does not have a girlfriend. The 31-year-old lawyer consciously chooses not to enter into a relationship. He is often far from home for long periods of time, as many of the people he helps live in the countryside. And more importantly: he would not want to expose a wife and children to the dangers of his work. Family members of human rights activists often face reprisals.

Colombia is now being advertised on tourist websites as a beautiful and safe holiday destination. According to Rommel, the reality for many residents is nothing like that. “In the tourist spots, the tensions are less noticeable,” he explains. The Santos government also actively promotes the idea that – since the peace agreement with the FARC in 2016 – the civil war has ended. He sees this completely differently. “Political violence continues unabated. For farmers and social leaders, for those who stick their necks out, nothing has changed. Nothing at all. We are back in the period of great violence. The sixties, seventies, the time of ‘la grande violencia’.”

Congressional elections were held on 11 March. “The right-wing reactionaries won. It is clear to human rights activists like me and other activists that in practice, a ‘social genocide’ is taking place.”

Murders

Rommel has no doubts about the source of the violence: “the government and the paramilitaries, who work hand in hand with the government. In the eyes of the government, paramilitaries have not existed since 2005. But in reality, they are more active than ever.”

Is he not afraid to make such strong statements? A gesture by Rommel indicates that he has no other choice. “Of course, I may be prosecuted for speaking out so clearly. But there must be an end to the violence, to the killing.” According to Rommel, more than two hundred human rights activists and social leaders were killed last year. “And that number is more or less constant. Every year there are that many victims. The government does not recognize the murders. They keep such figures hidden, in the dark.”

In theory, lawyers can request government protection. There is even an official ‘protection unit’, the Unidad Nacional de Protección. Rommel shrugs his shoulders. “In fact, the state is in the process of withdrawing the protection afforded to human rights activists. It argues that the civil war has ended, the violence has ceased and we are now in a ‘post-conflict’ situation.”

Social inequality

The internal struggle that has plagued the country for decades is complex. It is based on the conflicting political, economic and ideological backgrounds of the many parties involved: the state, the army, paramilitaries and the largest group, the poor, small farmers and indigenous populations who are the main victims. These are also the people Rommel represents. “Colombia’s core problem is social inequality and injustice, the lack of any recourse, the pointlessness of reporting crime. In some regions there is complete impunity. ”

The current violence is mainly about land ownership. Rommel explains that during the war many farmers were forced to leave their land or to ‘sell’ it at bizarrely low prices. “The state, paramilitaries, national companies and multinationals – all with their own interests – aided in this.”

A law passed in 2011 was intended to return that land to the original owners. “The law – known as the Restitution Act 1448 – was seen as a major development in Colombia. But in practice, the law is inadequate and illusory. Lacking official documents, on what can the original owners base their claims? The current ‘owners’, which include companies and ‘projects’, have the power, influence and money to block any such claims. Politicians, the military and economic leaders maintain this status quo. Violence was used to appropriate the land and is now being used again to retain it.”

Stigmatization

Lawyers who defend the interests of the little guy, political prisoners or those reporting human rights violations do so at great risk. According to Rommel, they are associated with the parties they defend, or are falsely accused of (and sometimes prosecuted for) corruption, fraud or undermining justice. “When we give legal assistance to political prisoners, we are stigmatized as terrorism lawyers. We also help family members of people who have been executed by the army without any form of trial.”

According to Rommel it is impossible to overemphasize the importance of international attention, such as the Caravana the Juristas. “With this support, we are in a stronger position to confront the authorities with regard to our security risks. They must be convinced that we are not parties to the conflict, but are only using the legal system to combat lawlessness.”