“Change will come, even if it will be after me”

Text: Johan van Uffelen

Photo: Peter Beijen

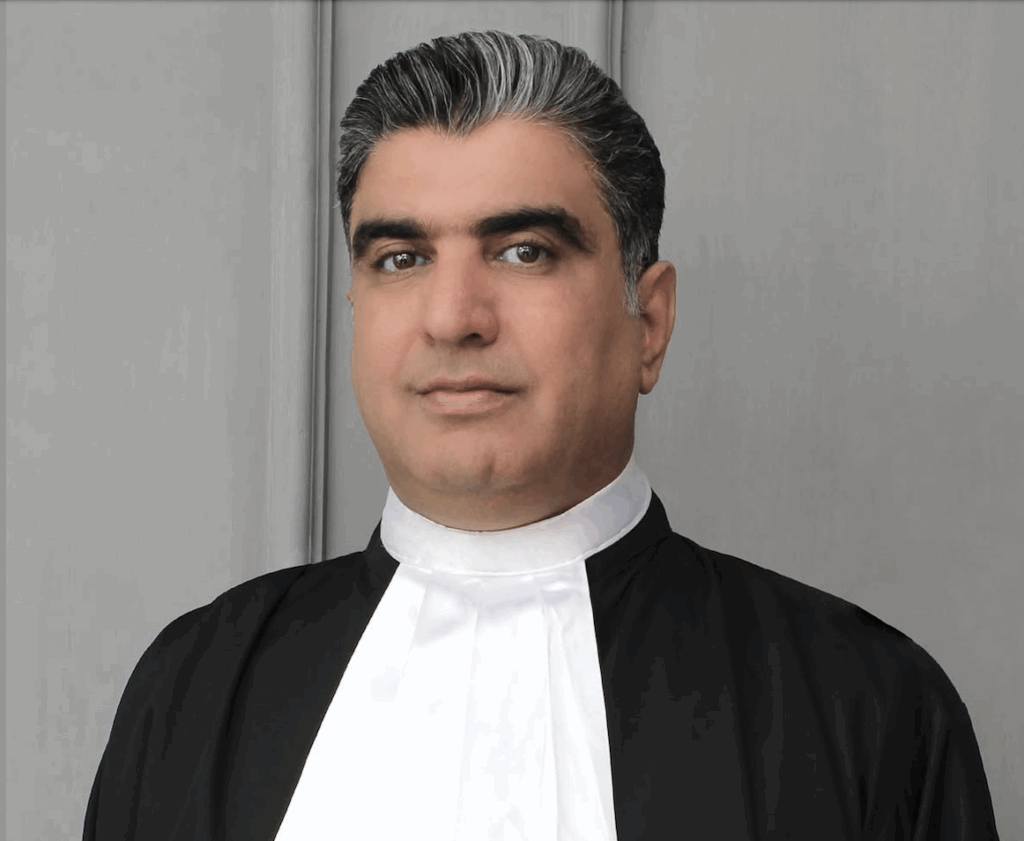

Amsterdam, commonly referred to as the epicentre of sexual freedom. October 11, International Coming Out Day. It is no coincidence that Lawyers for Lawyers has invited Michel Togué to come to the Netherlands on this particular day. The 52 year old human rights activist is one of the few lawyers in Cameroon who dares to defend LGBTQ+ people.

“Imagine”, he says in the lobby of his modest hotel, located at the site of an old naval wharf in the Dutch capital. “I’m the chairman of a Cameroonian forum of human rights defenders. When I bring up LGBT-cases during our meetings, people say: That is not about human rights. Can you believe that? They are all human rights defenders.”

Together with his colleague Alice Nkom (74) he represents many victims of sexual and gender discrimination in his country. Both are the founders of the human rights organization ADEFHO (l’Association pour la défense de l’homosexualité). Michel has been a member of the Cameroon Bar Association since 1999. He is a human rights lawyer with 23 years’ of experience as an activist, adviser and attorney. His curriculum vitae, full of international commendations of his courage, is just as impressive as his non-verbal communication: Togué masterfully supports every word with expressive facial expressions and hand movements.

The ignorance and fear among some of his colleagues is no outlier. Michel’s office has been broken into several times, his computer and client files stolen on multiple occasions. He and his family frequently receive threatening, anonymous phone calls and text messages – including even numerous death threats. The reason behind these messages is clear: his work defending LGTBQ+ people in court. The harassment extended to his wife and children. By 2012, these unending threats had become so severe that Michel was forced to request asylum for his family in the United States. His family now lives in the United States, where Michel tries to visit them two or three times a year.

Afraid

What makes him such an ardent advocate of people with a different sexual preference? “Actually I myself, I don’t know why. As a matter of fact this kind of discrimination is no discrimination in the literal sense of the word. Because when you discriminate you have some reason. This is fake discrimination because people who act like this have no reason. But the results of their attitude are even worse.”

Discrimination based on sexual behaviour is legal in Cameroon. In fact, article 347.1 of the Penal Code prohibits sexual intercourse with a person of the same sex. Cameroon and Uganda are the two countries where homosexuality is prosecuted more than any other country on earth.

Is there no political opposition to such laws? A wry smile from emerges from behind his gold-coloured glasses. “The law has been issued by the government. The opposition parties are afraid to openly support gay people.”

Togué states that there is a lot of international pressure on the government, as this kind of discrimination all too often violates people’s basic human rights. “The government doesn’t deny, but they say: It is not yet time for our society to accept homosexuality.”

Diabolical

Homophobia is widespread in Cameroon. “Gays and lesbians are also discriminated within their own families and neighbourhood. They can’t live their life at all”. He affirms that “It is true that this is a general feeling in society. People just don’t accept.”

It is often argued that this view is deeply rooted in the traditional culture of Cameroon, a taboo and a legacy of the area’s ancient beliefs and customs. But Michel strongly denies this: “That just doesn’t make sense. We share borders with countries like Gabon and Guinee. They don’t face this kind of discrimination, while we have the same cultural background. Besides, it has not always been like this. Article 347 has been in the law for a long time, but before it was barely known and not enforced.”

Togué sees two clear events which steered Cameroonian society towards homophobia. In November 2005 a teenager in the capital city, Yaoundé, killed one of his classmates with a knife. Once apprehended, he told the police that he had been sexually harassed by the victim. This caused widespread outbursts of anger. The anger was subsequently given a further homophobic direction by religious prejudices. A month after the stabbing, archbishop Tonye Bakot told Christmas-churchgoers that gay people don’t deserve compassion, because they are ‘diabolical people’. Michel leans forward, anger in his eyes “Can you imagine? Christmas ought to be about forgiveness, acceptance and tolerance.”

Five years imprisonment

Article 347 mentions penalties of between six months up to five years imprisonment for sex with someone of the same gender. “Thus formally you have to be caught during the moment you have intercourse. But that is not how it works in reality. Gays and lesbians are chased by the police. They are being arrested juist because of a denunciation, or their physical appearance. For instance in a case of two young boys who were arrested because the policeman assumed they were dressed like women.”

As people are rarely caught red-handed during their sexual activities, torture is a commonly used tool to extract a confession. “When you arrest someone without any evidence, but you pretend they are gay people, you have to force them to give in.”

What means do you, as a lawyer, have when this legalised discrimination is brought to court?

“That is a very good question. We defend the facts. There has to be proof of sexual intercourse. Fortunately there are some judges who are not homophobic. Not many, but there are some who follow our arguments.”

Animals

A Dutch documentary showed an organisation of young people who visit bars and other meeting places to collect proof against gays and lesbians. Surprisingly, their leader is a journalist. He says things like: Gay people are animals, they are devilish. And also: “There are two things that can provoke civil war in Cameroon: Closing bars and legalizing homosexuality.”

“O yes, I know this man… He is mad.” The human rights activist spreads his arms in impotent indignation. “A madman. But what can I do?”

Still, you carry on…

“Yes, I cannot leave. Being a lawyer means that you stand up for the people who need you, without any care of who they are. I receive threats because I fight sexual and gender discrimination, but when I defend a murderer I am not identified with him either? Perhaps I’m crazy. I could join my family. But I have such a strong conviction that I have to do this work. If I leave this fight there is no one left to take over. Alice Nkom is already 74. She needs my help. So I decided not to give up.”

You and Alice received the prestigious Dutch Geuzenpenning for your remarkable work. Lawyers for Lawyers supports you. What does this recognition of your work mean to you?

“This support is of tremendous importance for us. The threats are becoming less frequent. International attention makes your profile bigger. Being known makes you less vulnerable.”

Shaking his head, he adds: “I dream of the day this discrimination is banned in my country. I hope I can still witness this before the end of my life. I am sure this moment will come. Even if it will be after me.”

© Lawyers for Lawyers / Johan van Uffelen/Peter Beijen