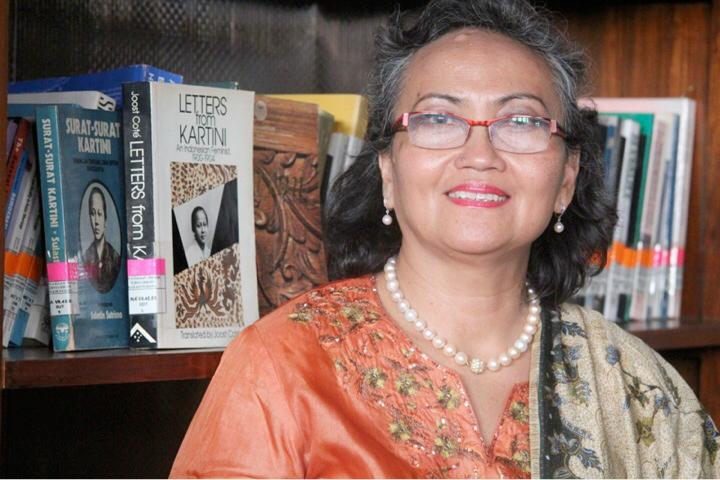

Lawyers for Lawyers presents the “Highlighting the Work of Female Lawyers from Asia” interview series. This series highlights the important work of inspiring female lawyers from Asia. We address the general challenges these lawyers face as women in the male dominated legal profession, solidarity and empowerment among female lawyers, examples of sexism in their work space and how they respond to those situations. In this edition we interviewed Nursyahbani Katjasungkana from Indonesia.

Nursyahbani Katjasungkana is a feminist lawyer and a human rights activist from Jakarta, Indonesia. In 1998, Nursyahbani was elected as the first General Secretary of Indonesia Women’s Coalition for Justice and Democracy, which focuses on the political participation and representation of women. Nursyahbani has further co-founded the Indonesia Legal Aid Association for Women (Asosiasi LBH APIK Indonesia/APIK). She was a member of the World Bank’s Advisory Council on Gender and Development from 2013 to 2015 as well as the contributor of Women, Law and Business of World Bank Group Yearly Report. In addition, she was the Indonesian prosecutor of the Women’s International War Crimes Tribunal on Japan’s Military Sexual Slavery in 2000, General Coordinator of The International People’s Tribunal on the 1965 Genocide and Crimes against Humanity (2015) and a panel Judge of The Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal on state crimes against the Rohingyas and other groups (2017). She was also panel member of Iran Atrocities (Aban) People’s Tribunal (2021-2022).

Nursyahbani is a strong believer that we as lawyers need to learn more about gender and law. This is what her organization (APIK) promotes, by giving trainings about law and gender or feminist legal theory and offering practical training to lawyers and other legal enforcers as well as to paralegals.

How did you experience entering (the male dominated) legal profession at the start of your career?

‘I started as a young lawyer in 1980 at the Indonesian Legal Aid Foundation, Jakarta chapter (Lembaga Bantuan Hukum-LBH Jakarta), a well-known human rights group at the time. There were already female lawyers working there, and I admired them a lot. All of them were my teachers at that office. I had no problems with entering the male dominated legal profession in terms of my career. My superior and colleagues were mostly male but it did not have any effects on my career. They needed only less than three months to promote me to Public Relations officer. I worked hard, my performance was good and I networked a lot. However, being a woman, I did experience problems in terms of handling cases. For example, I handled a divorce case and I was the lawyer of the woman. Even though she was the main caretaker of the children, the father was appointed guardian of the four children. The youngest was killed by his father and step mother. I filed the case and demanded the court to return the children to their mother and annul the parenthood of their father, and I won. The oppositions’ lawyer (a male whom I had known earlier) was furious at me and told me that I was too cruel and cold blooded by asking the annulment of his client’s parenthood right. This case shows that in some family law cases, men take the professional activities of female lawyers out on them personally. Besides that, I received criticism from my supervisory board member for handling family cases that were considered as intimate or private matters. However, discrimination and violence against women is an important topic at many levels: both at the level of society, at the regional and the national level, in parliament.’

Would you say that you face any challenges as a female lawyer working in Indonesia?

‘Not much as a female lawyer in general. The problem is when we handle cases concerning women’s issues. When we handle women’s issues, there is a possibility that we will be personally (both verbally and physically) attacked. I experienced that twice. For example, I was advocating for a woman and her husband was shouting at me outside of court: “Because of you, my wife is divorcing me. She does not know anything about her rights herself!” Another time, a man approached me with a knife, he wanted to kill me. I quickly went inside the court building. My director came to pick me up with his car after the court session; otherwise I would not have been able to go home, because the man who attacked me was waiting for me outside the court. I believe this kind of violence is worse against female lawyers than against male lawyers who handle women’s cases. Somehow a female lawyer is more easily identified with her client or with her client’s case.

Are female lawyers in Indonesia organized in associations or groups?

‘We have no female lawyers’ associations. However, there is a group called Indonesia Feminist Lawyers’ Club, consisting of male and female lawyers. They have been trained by the National Commission on Violence against Women some years ago. Even though no separate female lawyers organizations exist, training programs have been developed on different levels to spread awareness on the rights of women.

I think that in every bar association there is a division on issues related to women and children, but I am not familiar with their programs. I do know that they sometimes include women’s and children’s rights in special trainings for law faculty graduates who practice to become a lawyer.

Since its establishment in 1995, APIK has developed a special training on Gender and Structural Legal Aid for aspiring lawyers, staff members or paralegals of APIK Legal Aid offices. The aim of the training is to build the capacity of women’s rights advocates and organizations to transform discriminatory laws, policies and practices and increase women’s access to justice as well as to build a community of legal activists, lawyers, policy makers and implementers who are committed to advancing women’s rights through law. We aim to equip them with the knowledge, skills and networks to analyse and challenge discriminatory laws and practices against women. APIK believes that while law can be used to oppress women, it can also be used as an instrument to realise justice, equality and human rights. While using law as a powerful tool, APIK also recognises that law is not neutral and often shaped to reinforce the status quo of power relations.

Do male lawyers support their female colleagues when they experience unequal treatment or discrimination?

‘At least in our legal aid and feminist lawyers’ circle, yes. I believe that my male colleagues would defend me if I would experience unequal treatment or discrimination.’

If you could give advice to young female lawyers or law students, what would that be?

‘For female lawyers it is important to be independent and therefore, you should not be dependent on men but keep trying to cooperate with them to take a feminist path. Because the competition is so hard in this environment, just go on your own. Be yourself, be self-confident and follow your heart.

Another piece of advice for young female lawyers: do not only take on cases, but also try to advocate for policy change. That way, you will not only change the life of your own client, but hopefully that of everyone. That way you will make a difference! I told this advice to Kotaro, my 9 years’ old grandson who asked me just a week ago : “grandma, how come that you are so popular and well known?” I told him: be brave, honest, and make a difference!’

***

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this interview are those of the interviewee and the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Lawyers for Lawyers.